One of the nice things about having my own blog is that I get to write about whatever the hell I want, and nobody can stop me! And today, I feel like talking to you about video games. One video game in particular, actually: Echoes of Wisdom, the latest addition to the Legend of Zelda series.

I’m no old-school Zelda nerd, having hopped onto this game franchise’s bandwagon with 2017’s Breath of the Wild, the open-world adventure often heralded as one of the best video games of all time. But I’ve become a big enough fan since BotW that I was thrilled when the team announced Echoes of Wisdom – especially since it’s the first main-line Zelda game where you actually get to play as Zelda.

Inevitably, there was Discourse about this choice. I didn’t go looking for it, because I’ve read more than enough “Women ruin everything with wOkE!!1!” tweets to last me a lifetime. Never mind that the series’s usual hero, Link, was specifically designed to be androgynous-looking so that players of all genders could relate to him better – there will always be gamer bros who think diversity and social progress are the enemy, and I’m happy to let them keep playing in their tiny little sandboxes while the rest of the world grows up and moves on.

I follow many Twitch gamer boys who are not insufferable misogynist assholes, however, and I found it delightful to watch their first playthroughs of Echoes. No one said a damn thing about it being weird to play as a girl. Instead, some of them exclaimed, with smiles gleaming and controllers clacking, “It’s so cool that you get to play as Zelda in this one!”

Having played through Echoes myself, I see it as a feminist allegory – and not just because you play as Zelda. I have no idea how intentional this was on the part of the creators, but I do know that this is the first Zelda game to have been directed by a woman, which is telling!

Let me give you a breakdown of some of the things I noticed when playing Echoes through a feminist lens. (Spoilers ahead!)

Your (evil) heroes & protectors

(Content note: brief mention of sexual assault + harassment)

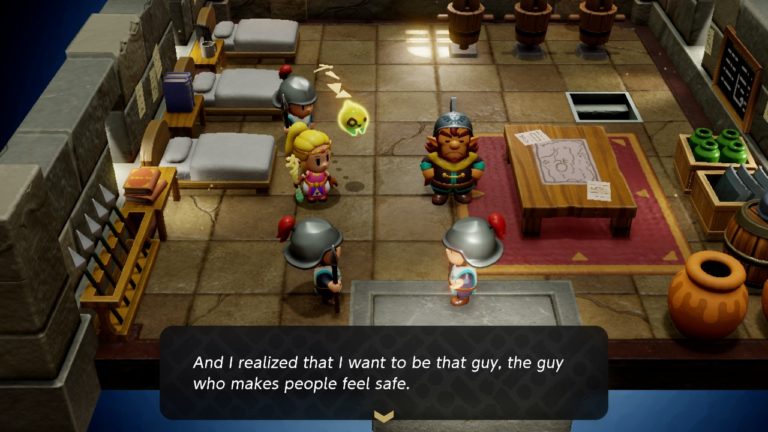

In some of the first plot points of the game, Link – who has rescued Zelda from harm countless times before, and is her literal heaven-sent protector – gets stolen away by an evil entity. Left in his place is a body-snatcher-style copy of Link, who has all of Link’s raw power and battle skill, but none of his warmth and goodness. His eyes, once friendly and kind, glow red with rage now. He may have saved her life a hundred times, but now he wants to end it.

“Dark Link” is one of the first bosses you face in the game, and I found this fight genuinely chilling. It reminded me, viscerally, of all the times a seemingly-trustworthy man has shown me his true colors – whether by sending unsolicited dick pics to my friends, going on a random slut-shaming tirade, or (yup) touching me in ways I hadn’t consented to. It’s deeply unsettling when this happens, and it can and does shake the very foundations of my ability to trust anyone.

Similarly, Zelda’s own father – the king of Hyrule – is also replaced by an evil body-double, who immediately declares Zelda a criminal and has her thrown in jail. All of the men Zelda should be able to trust are working against her at every turn, with hatred in their hearts. Like, damn; what a #relatable #mood.

Resourcefulness as a virtue

The main gameplay mechanic in Echoes is the ability to create, well, echoes – illusory copies of various objects and monsters, which you can use for both combat and puzzle-solving throughout the game. This stands in stark contrast to most Zelda games, where you play as Link and can raze down enemies yourself, with your sword or bow.

Whereas Link’s god-given power is courage, Zelda’s is wisdom (hence the title of this game). I was reminded, while playing, of the Audre Lorde quote about how “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” While I agree with that brilliant sentiment in matters of real-life inclusion and activism, it’s interesting to see how Zelda literally uses the tools of her oppressors against them throughout this game. She can send a flaming bat flying at Dark Link’s head, or hide in a clay pot to sneak past prison guards, or sic a band of murderous lizards on the jacked centaur trying to unalive her – but only after she’s “learned” these echoes, often from her enemies themselves.

This very much reminds me of what some feminists might call “working within the system” or “playing the game” – like when, for instance, a female employee maintains a sweet smile and pleasant demeanor while strategically talking her male boss into giving her a raise, in such a way that he almost ends up thinking it was his idea, since that may be easier on his ego.

There are major limits to this type of strategy, as the Lorde quote makes clear, albeit in a different context (she was talking about race and intersectionality in feminism). But it makes sense to me that someone like Princess Zelda would be shrewd and crafty in fighting her enemies, especially since she doesn’t wield traditional weapons like Link does, and doesn’t have control over the royal military like her father does.

Power is all but inaccessible

Despite being the widely-renowned princess of the realm, Zelda doesn’t have much power, neither physically nor politically. As I’ve described, throughout the game she mainly fights by summoning echoes of objects and monsters that can do direct damage, since she herself cannot.

Well, actually, there is one way that Zelda can do direct damage without summoning an echo… but it involves transforming into Link. (You know that thing about how disguising yourself as a man can help you get ahead as a woman, because the patriarchy is stupid? Yeah, that’s a thing in video games too.)

There’s a mechanic called “Swordfighter Form” in which Zelda becomes a spectral copy of Link, capable of hurting enemies with his sword, bow, and bombs. But crucially, you can only stay in this mode for maybe 10-20 seconds at a time before your “energy” runs out, and you morph back into Zelda. These short bursts of Link-time are especially helpful in boss battles, but Swordfighter “energy” is rare enough that many players (myself included) don’t end up using this mode in normal gameplay very often.

Some of the Twitch boys I follow were very complimentary of the game overall, but noted that it would’ve been more fun if you could take more direct control over combat, like in a traditional Zelda game. They said it sometimes felt tedious to wait around, dodging enemies and watching your echoes beat them up for you, instead of jumping in and joining the fight.

Me, though? I didn’t find those parts of the game tedious at all – maybe because combat is rarely my favorite part of any game, or maybe because watching echoes kill monsters was fun for me in the same way that watching robots fight goblins was fun in Tears of the Kingdom. But even setting aside the gameplay aspect, I think it makes sense thematically for Zelda to only have limited access to power – because she does. We see at the beginning of the game that even being the fucking Princess of Hyrule can’t protect her from anything – her own father throws her in the clink, making up elaborate lies about crimes she’s committed, and everyone just… believes him. Zelda is forced to become a fugitive in her own kingdom, because her father has real power, while she herself – as a princess and a young woman – does not.

So, while those Twitch fellas’ hearts are in the right place, I couldn’t help but chuckle when they said it was frustrating to be stripped of their power and agency. It’s been frustrating for a hell of a lot of women, too – for centuries, or millennia, before the Zelda series was even a twinkle in Aonuma‘s eye.

“She rescues him right back”

The game begins with Link saving Zelda, and ends with Zelda saving Link. I love this; it’s kind of perfect, and reminded me of the end of Pretty Woman, where Richard Gere climbs Julia Roberts’ fire escape like a gallant prince seeking his princess:

Edward: So what happened after he climbed up the tower and rescued her?

Vivian: She rescues him right back.

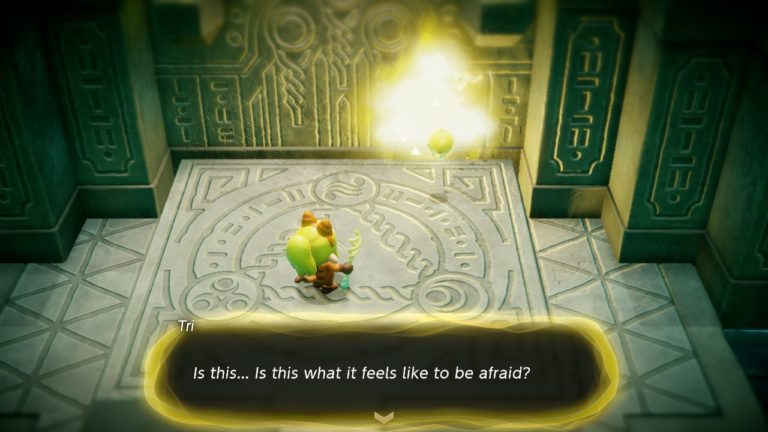

In Echoes‘ case, some might call it a predictable ending for this Zelda-centric story, and yet it also feels like the only way it could’ve/should’ve ended. And it gestures at one of the biggest lessons I’ve taken away from the feminist movement as a whole: that true progress, safety, and joy are found only through collaboration and interdependence – and that people of all genders need help sometimes, and people of all genders can provide that help. We’re more similar than we are different, and we’re stronger when we acknowledge that.

This isn’t a review of the game, but if it were, I would tell you that it’s fun, engrossing, has cool mechanics and a kickass soundtrack, and encourages creative problem-solving – so, basically, it’s a banger.

But with all of that being said, I think one of the coolest things about Echoes of Wisdom is that it’s a story about womanhood, directed by a woman, in a series where a woman has long been the figurehead and MacGuffin but never the hero. Players have been rescuing poor helpless Zelda for decades; this latest version of her can save her fucking self, something I always wish more women felt empowered to do. But that is why we fight, and that is why we will continue to fight.

The books, as it turned out, were

The books, as it turned out, were  So many times, I have told a partner, “Making me come is difficult,” when what I meant was, “I know exactly what’s required for me to get off, but I’m scared you don’t care enough to learn how to make it happen, so I’m not even going to try to teach you.” I have often said, “Don’t worry about making me come, I’m fine,” when what I meant was, “I don’t feel entitled to pleasure, even though I believe you are.” I still often say, “It’s probably not going to happen tonight,” when what I mean is, “It could happen if you did what it takes to make it happen, but I’m too embarrassed to show you how to do that, or to ask you to work that hard for me.” Meanwhile, I’m still giving diligent blowjobs left and right, time and effort be damned. It’s inequitable and it’s unacceptable.

So many times, I have told a partner, “Making me come is difficult,” when what I meant was, “I know exactly what’s required for me to get off, but I’m scared you don’t care enough to learn how to make it happen, so I’m not even going to try to teach you.” I have often said, “Don’t worry about making me come, I’m fine,” when what I meant was, “I don’t feel entitled to pleasure, even though I believe you are.” I still often say, “It’s probably not going to happen tonight,” when what I mean is, “It could happen if you did what it takes to make it happen, but I’m too embarrassed to show you how to do that, or to ask you to work that hard for me.” Meanwhile, I’m still giving diligent blowjobs left and right, time and effort be damned. It’s inequitable and it’s unacceptable.